Nowadays, the 1990 NBA Finals inspire neither awe nor reverence (outside of the two finalist hometowns). It is not considered a “classic” as it didn’t go 7 or even beyond 5 games.

It should not be overlooked for three reasons.

For one, it produced 4 close games, a thrilling comeback, an overtime game, and a waved-off buzzer tying game.

Two, it would cement the legacy of one team and player (Detroit and Isiah Thomas), while eternally marking another as a perennial, unappreciated bridesmaid (Portland, Clyde Drexler).

Third, the series would bridge the NBA from the dominance of the Magic-Bird era (as neither man-made even the conference Final in 1990), while keeping Michael Jordan on the cusp of ruling the NBA. Strangely enough, as of 1990, Jordan had yet to taste an NBA Final, yet he would be a hidden figure in this matchup between two underappreciated teams.

For Detroit, their greatness would become magnified over time for beating Jordan’s Bulls. For Portland, they would be forever regarded as disappointing for not winning like the Bulls later did. But that lay in the future.

For the two teams that comprised the 1990 NBA Finals, the way both teams built for the moment (drafts, trades) had been both similar and different.

Both teams would be led by two exceptional men (Isiah, Drexler). But while one was an unprecedented franchise player, the other had been an unwanted one.

Trader Jack and the Unprecedented Superstar

The irony about the 199o NBA Finals Champion Detroit Pistons was that its architect, John William McCloskey, had in fact spent 3 years as coach of the expansion Portland Trailblazers.

Portland was an absolute wreck; Much of it was because of the historically awful drafting of LaRue Martin in 1972. McCloskey would be released before Portland corrected this by drafting Bill Walton, but it taught him some building lessons. At the time, the correct thing to do to build a team was to draft a talented big and worry later about his skill or commitment to excellence.

Martin had neither, and so when McCloskey took over the equally bad Detroit Pistons in 1979 as GM, he looked for both traits in his ideal franchise leader. It would take a few years, but he found his guy in a University of Indiana player Isiah Thomas.

There were two problems with this. McCloskey wanted to build a champion, and Thomas was “generously” listed as 6-1 (likely more 5-10). This defied the conventional wisdom that a man that small could be the franchise foundation.

But Thomas was a rare player. He was exceptionally fast, fearless, a ball-handling savant, and would literally do anything to win a basketball game (this would eventually make him both the eras most unpopular but authentic superstar).

Also, he had a near maniacal rage about winning, and he was unafraid of looking foolish in pursuit of that.

For instance, he already insulted the Dallas Maverick organization, referring to them as “cowshit kickers.” This was by design; The Chicago raised Thomas had no intention of playing anywhere in the deep south, thus his comments.

He also didn’t want to play for Detroit, as they were a team with no established identity or tradition; He told McCloskey “What would you do if I said I didn’t want to play for the Pistons”? McCloskey replied, “Well, we will draft you anyways” and promised to surround him with the requisite talent to succeed.

McCloskey was supposed to be offended; instead, he knew he had his man. Now, he had to build a nucleus around him.

Weeks into Thomas’s career, he found the perfect soul mate for his new star. It was in the form of a tall, awkward player he scouted at the aborted 1980 Olympic Trials. His name was Bill Laimbeer, and McCloskey thought of him as something of a joke, a second-tier player not cut for the NBA.

Now, 16 months later, he studied Laimbeer the man as well as the player. He came with a different perspective. On the surface, Thomas could not have been more different than Laimbeer.

Thomas was short, while Laimbeer was tall. Thomas was temperamental and wore his feelings on the surface. Laimbeer was excitable but also a very closed individual. Thomas was a devout Catholic, a Democrat who would behave like, well a Chicago Alderman (good and bad). Laimbeer was like the wrestler who was an embarrassment to the country club jet-set crowd. Thomas was hood, while Laimbeer it was said actually made less as a player than his executive father.

But, under the surface, the two had plenty in common. Both men were the kind of players that you would want on your team if you were drawing sides.

Both men were very intelligent, with high basketball IQs. Both men got the best of their abilities, as Thomas would become the best ever at shooting over 7-foot men. Meanwhile, Laimbeer became one of the early students of the arc of the basketball, and in turn, became an exceptional rebounder.

The two became both roommates and soul mates, and the foundational blocks to the Piston turnaround.

Shortly thereafter, they would add the third piece; He was a Brooklyn-raised volume shooter named Vinnie Johnson.

Detroit, who won 21 games, now had a young nucleus that improved by 18 games. And Thomas was a revolutionary, the first unquestionable franchise piece at his size.

McCloskey still had plenty of work, but the start was great. All three men would play a key role in the 1990 Finals.

The Unwanted Franchise Player

It is almost a shame that Clyde Austin Drexler never was totally appreciated. He today is largely remembered as the reason Jordan didn’t become a Portland Trailblazer and even in that franchise isn’t considered its best player ever.

Part of this is because Drexler wasn’t wanted by his inaugural coach, who held to the traditionalist view that a team should build around a center.

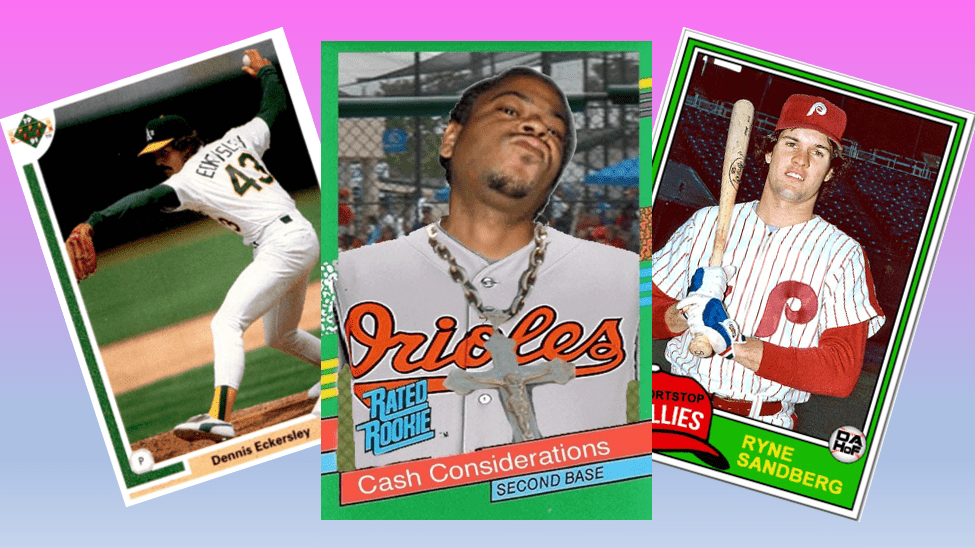

Also, because drafting the supposed franchise savior in Sam Bowie turned into disaster ignores the awesome job Portland did drafting and trading their way to the 1990 NBA Finals (turning Bowie into Buck Williams, a player coveted by Jordan).

Drexler’s problem was really a conflict between Coach and management. General Manager Stu Inman and scout Morris “Bucky” Buckwalter had fallen in love with Drexler, seeing him as a new Julius Erving. The problem? The coach, the iconic John Travilla Ramsay didn’t agree.

Ramsay, known as Dr. Jack, didn’t feel Portland needed a guard or small forward, Drexler’s positions; he felt the position secure with All-Star Jim Paxson. Ramsay had made his name winning with undersized great centers, Bob McAdoo in Buffalo and especially his prize Bill Walton. He saw Drexler’s athleticism while also believing he was basically a dunker who would get exposed in a half-court game (he was right in this regard).

Drexler was extra space, not the way forward as far as he was concerned. This contributed to the disastrous Bowie drafting; In effect, Portland went traditional in 1984 NBA Draft after defying the odds in drafting Drexler the year before.

Drexler would never forgive Ramsay for this, and in the three years, they worked together clashed mightily. This obscured the fact that (Bowie notwithstanding), the Blazers had done a magnificent job drafting other need positions.

They were: Jerome Kersey in 1984, Terry Porter in 1985. Porter would team with Drexler to arguably give Portland the best backcourt in the Western Conference by 1990 and with Kersey (a great transition player), Portland had the makings of a very exciting team.

The problem? They would have to find a way to beat the best team of the era, the Los Angeles Lakers. This was easier said than done.

They Laughed: Building From Within

When Isiah held his first pro press conference, he said he wanted to build a team with tradition like the Lakers and Boston Celtics. This drew raucous laughter from the assembled press, but Thomas was determined.

After his rookie year, he attended every single Laker final. This was made easier by the fact that his best buddy Magic Johnson was on the Lakers. Thomas wanted to know the Laker secret; the formula required for success. Johnson, though told him he would have to find out on his own.

Rebuffed, Thomas would find his source within another sport. He was smart enough to realize that his Pistons would never be loved like the Lakers, Celtics, or Jordan’s emerging Bulls. He basically took the football model by seeing the Lakers as the Dallas Cowboys, and the Celtics as the rugged Pittsburgh Steelers. Jordan’s Bulls would be the basketball version of the San Francisco 49ers.

What about the Pistons? Well, suddenly Thomas became very enthused with the Oakland Raiders and Al Davis. The Raiders were popular because they were infamous. Nobody, however, denied their success. Moreover, the Raiders had success against all three of the other franchises.

Thomas had his answer and blueprint. His Pistons would thrive in their unpopularity; They would become the “Detroit Raiders” and finally the “Bad Boys.”

Davis, who lived for attention, loved the idea. Whenever the Pistons were in LA (where the Raiders were then based) Davis would generously allow the Pistons to use the Raiders training facility and staff (which helped them in the 1988 and 1989 NBA Finals).

The Pistons had their identity.

Showtime Without Kareem

The Trailblazers also looked to the Lakers for inspiration. After all, “Showtime” had been a modified version of the system Ramsay ran in Portland, with Kareem Abdul Jabbar excelling (and exceeding) in Walton’s role.

The problem for Portland is that after Walton’s feet fell apart, the Trailblazers never found a real replacement for him. The first attempt had been by Mychael Thompson (father of Splash brother Klay Thompson). Thompson had been a gifted but goofy player, and he seemed uninterested in dominating unless he was playing his old college buddy Kevin McHale. He was, in NBA speak, “soft”.

Bowie was a disaster, and his replacement Steve Johnson was solid but hardly an anchor at center. As a result, Portland had a great running team but one that would crumble in crunch time.

This flaw would overshadow the great drafting management did. Portland would finally find a more desirable center in Kevin Duckworth; Duckworth, though, was a 300-pound center who loved to shoot 18-20 jumpers in an era where a man that large was expected to bang inside. He was a very good addition to the nucleus but did not solve their main issue.

So, Portland, instead of greatness, jumped to very good and then fell again (to 39-43) in 1989, only to be swept in round one by the 2-time champion Lakers.

Finally, Portland found a sucker for Bowie and traded him on June 24th, 1989 for Buck Williams. Williams was a tough player and a magnificent rebounder and defender. The team would be complete for a 1990 NBA Finals run.

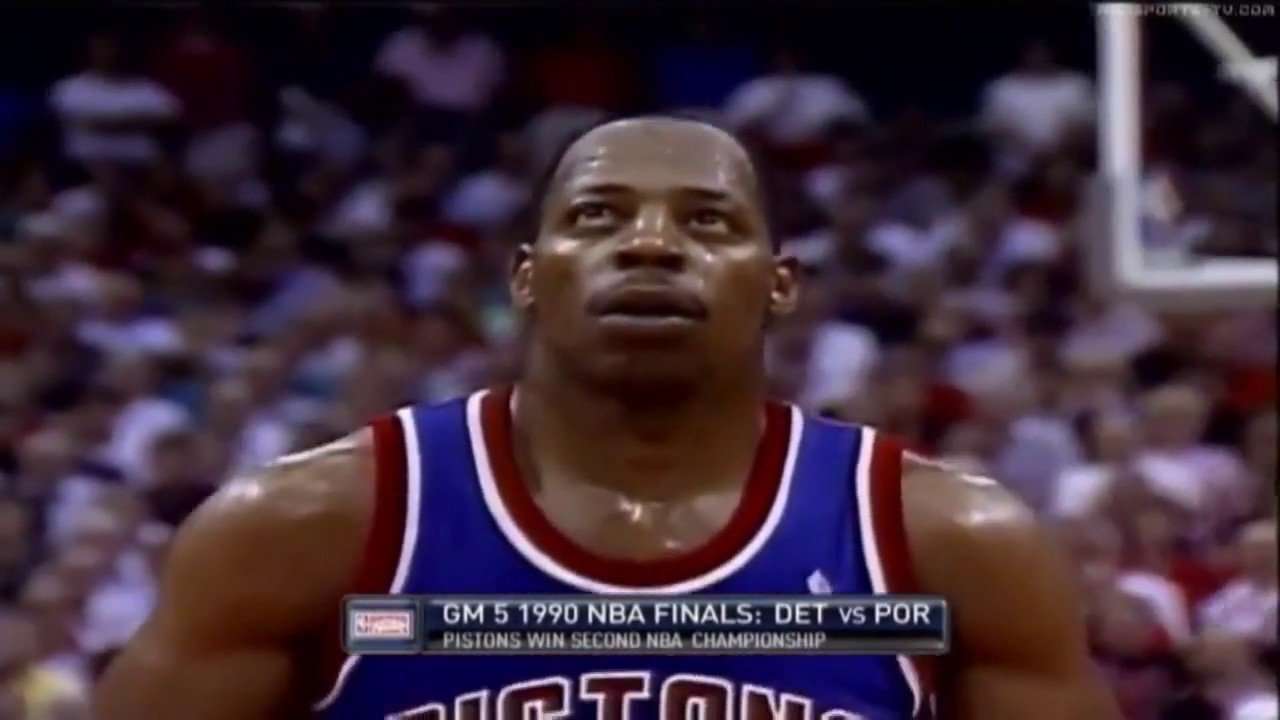

1990 NBA Finals: Pistons Go Back-To-Back

This was the first NBA Finals since 1979 not to involve either the Los Angeles Lakers or the Boston Celtics, and one of two NBA championships of the 1990s won by a team other than the Chicago Bulls or the Houston Rockets (the other was won by the San Antonio Spurs in 1999).

The Pistons became just the third franchise in NBA history to win back-to-back championships, after the Lakers and Celtics.

The Bad Boys won in 5 games.

Game 1: 105-99, Detroit

Game 2: 106-105 (OT), Portland

Game 3: 121-106, Detroit

Game 4: 112-109, Detroit

Game 5: 92-90, Detroit

Game 5 created the indelible, most memorable, moment and defining image of the series Vinnie Johnson’s game winner.

With 10 minutes to play in the game, the Blazers led 76–68. Then The Microwave Vinnie Johnson heated up.

Johnson scored seven points in Detroit’s 9–0 run to close the game and the series. His last shot was a 15-footer from the right sideline with Jerome Kersey draped all over him and 0:00.7 showing on the clock.